CPO or no CPO?

Chief Portfolio Officer of no Chief Portfolio Officer?

In 2013 CIO Magazine published the article by John van Rouwendaal on the ‘Chief Portfolio Officer’. Nine years later this topic is still current and John has added a small paragraph related to healthcare. The occasion for this (re)publication is the ‘Harvard Business Review Live Webinar: The Rise of the Chief Project Officer’ on October 26-th 2022.

It is practically not smart and theoretically incorrect when a CIO also takes on the role of the Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO). Nevertheless, this is daily practice within many organizations and this creates problems. Why is it that very few organizations recognize the CPO as a separate role?

A striking example of where the overlap of CIO and CPO roles cause problems can be found within the Dutch central government. It was a good idea to appoint a CIO for each department, but it was not sensible to also make the departmental CIOs responsible for project portfolio management (PPM). For the one who is responsible for IT it is simply impossible to take on the responsibility for the ins and outs of all programs and projects. Programs and project always entail far more than just IT. Therefore, the project portfolio requires attention from a broader perspective and at the highest organizational level.

Practical plea for a CPO

For years, experienced experts advocate the role of a CPO. For example, in 2003 PM Solutions writes that “Ideally, organizations should strive to have a CPO sit at the director or vice-president level with other senior executives in the organization. This position provides project oversight in virtually all areas of the organization, managing corporate level projects and overseeing corporate-wide resource distribution and allocation on all projects.”[1]

In 2004 out of the corner of the International Project Management Association (IPMA) came the recommendation: "Organizations which over a longer period of time spend twenty percent or more of their total budget on projects benefit from the introduction of the CPO model. This is to ensure that the capital is invested usefully, necessarily and efficiently, pays off and – from the perspective of the increased risk – is adequately managed and, last but not least, that the entire project community of the organization is managed and developed with specific attention, in a balanced way and professionally. In short, the purpose is to ensure strategic consistency, cost savings, increase of turnover and teambuilding.”[2]

In 2009 Gregory Balestrero, president and CEO of the Project Management Institute (PMI) spoke out in favor of a CPO in the context of the American government: “There must be significant scrutiny to ensure that these projects [hundreds of initiatives that are critical to our nation's safety and security] will get done according to plan and, more importantly, yield the outcomes that are intended. (..)There must be significant scrutiny to ensure that these projects will get done according to plan and, more importantly, yield the outcomes that are intended. (…) The president [Obama] needs what every CEO would need in this situation: a chief portfolio officer.”[3]

Awareness all around but still for example Wim van Ravenhorst notes in 2009 that "There are very few organizations [are] in which the importance of projects is recognized in such a way that the design and implementation of projects is secured as a strategic value at the highest level, for example, in the position of Chief Project Officer.”[4]

As recent as 2011 Peter Parks of the Association for Project Management (APM) notes the same: “Although many organizations now have a CEO, CIO, CTO and COO, and some even a chief engineer, few to my knowledge have a CPO, as in a chief projects officer, with responsibility for oversight of their investment portfolio. This task of ‘doing the right projects’ often falls to a CAPEX (capital expenditure) committee, usually reviewing projects as they arise rather than looking across the portfolio.”[5]

In broad outlines there is some agreement on what the CPO should have as tasks and responsibilities. Remarkably, there is no agreement on where the abbreviation ‘C.P.O.’ stands for. However, in the project management discipline everyone does agree that is does not stand for Chief Procurement Officer, Chief Performance Officer, Chief Personnel Officer, Chief Process Officer et cetera. But there is no agreement on whether CPO stands for Chief Project Officer, Chief Program Officer or Chief Portfolio Officer. Probably, this can be explained by the fact that thinking about portfolios is more recent than thinking about programs which, in its turn, was preceded by thinking about projects. When we look at it in this way, nowadays the abbreviation CPO stands for Chief Portfolio Officer. I consider it a missed opportunity that the makers of PRINCE2 (Cabinet Office, formerly OGC) didn’t end the discussion about the abbreviation with the publication of their best practice approach to PPM (Management of Portfolios). So now it is up to us: Let’s agree that from now on CPO stands for Chief Portfolio Officer.

Theoretical plea for a CPO

The need to secure the organization’s project portfolio management (PPM) at the highest level is not only endorsed by practitioners, but also by those who study and analyze this matter from a more scientific or theoretical perspective.

In 2000 PPM guru Harvey A. Levine already states that “(...) [W]e must add to the cadre of “chiefs” to which we entrust the success of enterprise. We must add a Chief Project Officer (CPO) (…) to lead the organization in meeting its project portfolio objectives.”[6]

Professor Paul Chapman of the Saïd Business School of the University of Oxford writes in 2009 that “the recognition of the CPO [Chief Programme Officer] position is akin to the emergence in the 1960s/70s of the Chief Operating Officer, COO, a role which has subsequently been seen as a critical position that is broadly positioned along with the CFO as first lieutenant to the CEO on the executive team. In the case of organizations that are organized around programs the CPO seems like a likely substitute for the COO.”[7] Chapman has designed a complete educational curriculum for the CPO.

Finally, we present Professor Pieter Steyn van de Cranefield College of Project and Program Management. He founds his plea for a Chief Portfolio Officer on “A recent IBM survey [that] found consensus amongst CEOs that organizations are bombarded by change and that many are struggling to cope with the transformation.”[8] Steyn proposes that the CPO “should come from the ranks of the program structures where a cross-functional mindset is cultured and will significantly support the CEO, CFO and COO with strategic appraisals and reviews at the executive leadership level.”[9]

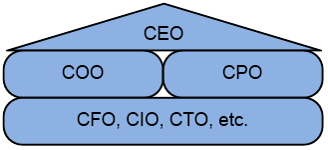

CPO versus CxO

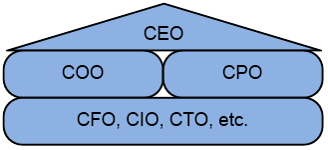

Several different designs are conceivable for the positioning of the CPO in relation to other ‘chiefs’. One approach is that of Marco Mud[10] (see figure 1). In his model, the CEO-CFO-tandem plays its existing role and is supported by the COO and the CPO. The idea is that knowledge regarding challenges on automation, procurement and legal affairs is dealt with in a problem-oriented way.

Figure 1

However, the method proposed by Mud does not do justice to (among other things) the role of the CIO. Information technology plays a crucial role in contemporary organizations. Both ‘business as usual’ programs and projects are full of IT, making it evident that IT knowledge should not only be dealt with in a problem-oriented way.

In an alternative model (see figure 2), the CPO is also positioned at board level as a counterpart of the COO. Where the COO is in charge of operations, the CPO leads the projects and changes. A notable difference with the first model is that the CFO is positioned differently. The CFO role is treated more as an integral role. The idea is that, like the CIO and other CxO, the CFO has a more 'horizontal' role to play in the matrix as opposed to the 'vertical' role the CFO now often claims. I can imagine what CFOs might think of this different positioning, but I believe it does more justice to their, in principal, simply (but no less complex or respected) facilitating role.

Figure 2

In 2020

At this moment [2013] the question is: Why a CPO? In 2020 the question will be: Why no CPO? The more organizations use programs and projects, the more CPOs will be appointed.

But beware: The CPO model knows a number of snags, for example:

- The other CxOs no longer feel responsible for programs and projects. However, the CPO has this in his own hands. He / she will continuously have to emphasize to his CxO colleagues that projects should not be seen as taking place 'on the other side of the fence, but as if happing ‘on other side of the playing field'.

- For a CPO to be able to take his responsibilities and exert influence it is crucial that (at least partly) a central budget for projects and programs is established. After all, who pays decides.

- A ‘new kid on the block’ will cause conflict. The current rulers within organizations will (and should not) give up their influence without a fight. But this fight should be fair and the outcome should serve the organizations interests. Guard against things getting personal or too political. And when things escalate and rationality no longer prevails, call for reinforcements as soon as possible. Or even better: Avoid misery from the outset by taking into account that ‘games’ will be played.

- A frequently heard problem is that the business and IT do not work well together. They do not understand each other, they throw unfinished affairs over the fence, et cetera. Introducing a CPO can cause similar problems to arise on an organizational level between operations and the project domain. The COO and CPO should therefore be best (professional) friends. They have to work together closely and constantly be careful not to grow apart. Moreover: "Good fences make for good neighbors" (Robert Frost). In other words: To be able to work well together it is necessary that it is clear where the boundaries lie. Roles, duties and responsibilities should be clearly defined.

Anno 2022

Nine years ago I hoped we would be further along in 2020. But the role of Chief Portfolio Officer is still only ‘emerging’. Hopeful is that almost a decennia later the role has not disappeared to the background. On the contrary, because even Harvard pays time and attention to it.

In healthcare I have not yet discovered a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) as described in this article. The executive that regards projects and project portfolio management as his responsibility and acts accordingly may, in may opinion, justifiably carry the CPO title. A CPO can also be a valuable addition to the ranks of the upcoming roles of CNIO (Chief Nursing Information Officer) and CMIO (Chief Medical Information Officer). Maybe we should then (also) be talking about a CNPO (Chief Nursing Portfolio Officer) and a CMPO (Chief Medical Portfolio Officer). The CNIO and the CMIO can focus on ‘running the business’ and the CNPO and CMPO on ‘changing the business’. On short term I don’t expect this to take off. Healthcare organisations (justly?) seem to be cautious and lagging when it comes to adopting new organisational developments. But maybe in 2030 we will be somewhere we cannot even imagine now. The importance of projects, good project management and excellent project portfolio management increases with the increasing speed of (needed) changes in healthcare. It might just be the case that in another decennia CPOs, CNPOs and CMPOs are quite normal. I would expect it, but personally I am not so sure of it as I was in 2013. I am hopeful though and I hope to write again on this topic in 2032.

References

[1] Bigelow, D., Does Your Organization Have a Chief Project Officer?, PM Network, 9-2003

[2] Mud, M., Chief Project Officer, IPMA Projectie Magazine, 06-2004

[3] Balestrero, G., Calling For A Chief Portfolio Officer, Forbes.com, 04-09-09

[4] Ravenhorst, W., Sturen vanuit het vakprojectmanagement, IPMA Projectie Magazine, 05-2010

[5] Parkes, P., Portfolio leadership and the chief projects officer, Apm.org.uk, 15-7-2011

[6] Levine, H.A., Need a CPO, The Project Knowledge Group, 2000

[7] Chapman, P., Educating major programme managers, 2009

[8] Steyn, P., The Need for a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) in Organisations, PM World Today – July 2010

[9] Steyn, P., The Need for a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) in Organisations, PM World Today – July 2010

[10] Mud, M., Chief Project Officer, Projectie, 2004